Tackling the troubled LTC facility

In a perfect world there would be no troubled long-term care facilities. But in the real world, administrators and directors of nursing (DONs) at some time in their careers might walk into a job turning around an underperforming or even a dysfunctional facility.

Sometimes the problems are clear before the first day of work, but at other times professionals walk in unaware of the situation. Someone has to fix the problems; the stakes for residents are very high. This could be a chance to become a hero, but it might also end a career.

DUE DILIGENCE

Before accepting a job, it is wise to investigate a facility, if the information is available. Look at the facility survey history, but beware. At the most current survey the facility is doing fine, but six months later it is a wreck. Reviewing public records and asking tough questions during the interview are minimal standards for considering a job. A walk through the facility can be very useful, but it cannot measure critical metrics such as staff morale or facility cash flow.

Ask why there is an opening for an administrator or DON (if both, beware!). An evasive answer of “our lawyers won’t let us talk about it” is a danger signal. Gauging the quality of the ownership is important. Bad governance may have caused the problem, or it may prevent the implementation of a solution. It is important to know these facts because it could be your license and your career on the line.

If the employer is upfront about the facility needing a turnaround effort, press for details as to the cause, the current situation, the ownership’s expectations and the time line.

WHERE TO START

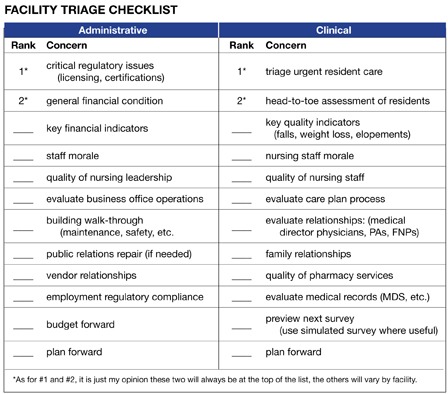

There is no checklist or “cookbook” approach to fixing a troubled facility. However, there are target areas and a systematic approach to problems is better than fighting fires. I would like to provide a framework for a systematic approach. I’ve developed a checklist (see figure) to use as a starting point, keeping in mind that no framework can substitute for direct assessment and your own homework.

Administrators must focus on everything; DONs will focus on clinical issues keeping one eye on personnel and budget issues. The approach will vary depending on the size, type and location of the facility and the type and quality of its ownership.

A DON needs a strong, capable administrator and an administrator needs a strong, capable DON. If either of the partners is less than capable, the turnaround effort will be more difficult. An administrator can replace a DON, but a DON is stuck with the administrator in the front office.

MORALE PROBLEMS

In a troubled facility, staff morale is probably low and could go lower. Management will ask staff to work harder and better while cleaning up past and current problems. Management will likely have to remove some staff members and discipline others. There is no magic bullet for bad morale, but leadership must at times supersede mere management.

What are the building blocks of facility leadership?

- Presence.Managers must be visible. This means rotating through every shift and rotating managers through the building weekends and holidays. This is not a 9-to-5 job.

- Participation.When the staff is struggling, spend a half-hour filling water pitchers, folding laundry, feeding residents or helping with activities to create a positive impression of management. Get out of the office.

- Praise.Staff will hear plenty about the facility’s failures and will often internalize those failures. Without being syrupy or phony, managers should accentuate the positives when they are obvious.

At times, it is necessary to evaluate and criticize. Deliver bad news in private. Terminating employees is agonizing for most of us, and cruelty or unprofessional behavior will echo through the halls into the sensitivities of remaining employees.

CLINICAL ISSUES

Governance and management failures will inevitably damage clinical care. A first step is to assess the current quality of care and to triage clinical problems. This must be done while continuing daily care, so hustle is required.

“Grand rounds” is not a quaint concept. A new DON must get a quick scan of care quality and begin to develop a list of problems, as well as order immediate action to correct serious quality failures. In addition to nursing grand rounds, the medical director should be asked to make grand rounds, perhaps in two or three sessions. During those rounds and the follow-up, the DON can gauge the quality and professionalism of the medical director and his or her ability to work with the nursing staff.

REGULATORY ISSUES

Regulatory problems may be looming or they may be (figuratively) nailed on the front door. Proper due diligence at the interview will at least allow you to know if the government is already involved. Ownership should have an ongoing relationship with legal counsel experienced in healthcare regulatory matters and with significant LTC experience. If not, now is the time to establish such a relationship.

If the government is not involved, such involvement may be imminent. Acting as if a survey is coming up would be a good mind-set for tackling facility problems. The most recent survey citations might be a good place to start, but they may also be out of date. Nothing is better than being on the floor, diving into the medical records, working through recent business records, evaluating staff and following through on problems.

If the survey is fresh or if there are jeopardy findings pending, the focus is clearer, but the timeline is less generous. The government may or may not give a little slack to a new management team, perhaps providing an opportunity for building fresh credibility. Two questions are critical: “Where are we?” and “What must we fix quickly?”

BUSINESS ISSUES

A troubled facility may develop into a financial exigency situation, or perhaps financial exigency created a troubled facility. In either case there may be multiple problems to solve, especially if the job entails improving quality of care while struggling with financial problems.

The new administrator must develop an understanding of the facility’s financial condition quickly, since problems tend to feed off each other. Determine if financial problems are causing care problems, and engage the ownership in developing a plan to solve the problems. Minimizing staff for financial reasons makes caregiving more difficult, but giving inadequate care may create greater financial jeopardy. If the facility is subject to financial penalties or reimbursement adjustments, the problems will compound.

TRIAGE THE SITUATION

TRIAGE THE SITUATION

Apply the medical concept of triage to the management and clinical situations. The checklist (see figure) provided might help to establish priorities, to set aside the non-problem areas and to formulate a plan for action.

CONCLUSION

Long-term care is difficult work under any circumstances, and there is no pausing to reorganize. Management must keep day-to-day operations on a high plane while working through inherited problems.

It’s not for the faint at heart.

Tom Ealey, a business professor at Alma College (Michigan), has 30 years of healthcare experience as a management consultant, seminar leader, writer and litigation analyst. He has worked with troubled organizations, including organizations in transition and those with regulatory compliance problems. For more information, email ealey@alma.edu.Jean Ealey, RN, provided technical advice for this article.

I Advance Senior Care is the industry-leading source for practical, in-depth, business-building, and resident care information for owners, executives, administrators, and directors of nursing at assisted living communities, skilled nursing facilities, post-acute facilities, and continuing care retirement communities. The I Advance Senior Care editorial team and industry experts provide market analysis, strategic direction, policy commentary, clinical best-practices, business management, and technology breakthroughs.

I Advance Senior Care is part of the Institute for the Advancement of Senior Care and published by Plain-English Health Care.

Related Articles

Topics: Articles , Facility management , Leadership , Staffing

TRIAGE THE SITUATION

TRIAGE THE SITUATION