2012 OPTIMA Award winner: St. Leonard Franciscan Living Community, Centerville, Ohio

A few years ago, St. Leonard Franciscan Living Community, a continuing care retirement community in Centerville, Ohio, faced the same challenges that other long-term care communities face when it comes to caring for the growing ranks of LTC residents with issues relating to Alzheimer’s disease: easily agitated residents due to the disease’s unpredictable patterns and mentally and physically exhausted caregivers.

Resident engagement centered around group activities and yet residents often became disengaged or bored, resulting in undesirable behaviors such as roaming, rummaging, anger outbursts and increased falls.

It was the falls issue among the general St. Leonard population that initially led Executive Director Tim Dressman to approach an ergonomics expert, Govind Bharwani, PhD, director of nursing ergonomics and Alzheimer’s care at the Nursing Institute of West Central Ohio at Wright State University. Dressman was looking for help to reduce resident falls and staff injuries in lifting and caring for residents.

|

| Dr. Bharwani meets with a resident at St. Leonard. Photo courtesy of St. Leonard. |

Ergonomics is the science of tailoring the environment to reduce stress on the individual. It is often applied in the context of physical stress on muscles and joints, but ergonomic solutions can also be developed to mitigate the effects of mental stress.

During his research at St. Leonard, Bharwani, together with his daughter, Meena, who works in healthcare technical consulting and process improvement, determined that residents with dementia required a specialized program separate from other residents. After lengthy observation they discovered that falls and other negative behaviors could be reduced through customized activities.

“A lot of people say it’s good to have eyes outside your industry looking in to have the most insight and that’s exactly what we did,” says Dressman. “Here we had a college engineering professor, who never spent a day in long-term care [find a solution]. He fell in love with [long-term care] and the families and residents in turn love him.”

The Bharwanis’ innovative approach to engaging residents with Alzheimer’s/dementia—Behavior-Based Ergonomics Therapy (BBET)—was pioneered in February 2010 in St. Leonard’s 18-bed Alzheimer’s unit. The BBET program addressed two strategic imperatives: to reduce falls in the unit and to design an Alzheimer’s care strategy that would be piloted in the unit and eventually reproduced across the continuum of care and in the expansion of memory care on the campus.

The Bharwanis’ innovative approach to engaging residents with Alzheimer’s/dementia—Behavior-Based Ergonomics Therapy (BBET)—was pioneered in February 2010 in St. Leonard’s 18-bed Alzheimer’s unit. The BBET program addressed two strategic imperatives: to reduce falls in the unit and to design an Alzheimer’s care strategy that would be piloted in the unit and eventually reproduced across the continuum of care and in the expansion of memory care on the campus.

|

| Meena Bharwani and Dr. Bharwani in the resource center. Photo courtesy of St. Leonard. |

Prior to the program’s implementation, an advisory board met monthly and included representatives from the community, faculty from Wright State University (an interdisciplinary team with members from the fields of nursing, gerontology and engineering), the Alzheimer’s Association, and family members and physicians. A separate cross-functional project team of facility staff and management met weekly to develop and implement the program. The team had a combined 90 years of hands-on Alzheimer’s care experience.

For the first objective, the project team drew the following conclusions based on research and observation:

- There was a higher occurrence of falls in the Alzheimer’s unit, not only because these residents are ambulatory, but also because their fall triggers were driven more by behavioral issues. Strategies that had successfully reduced falls by 25-30 percent in the other units had limited impact in the Alzheimer’s unit.

- Scheduled group activities were important for reinforcing a daily routine and providing opportunities for socialization but did not always hold the attention of all residents. If a resident became disengaged, it could become difficult for the facilitator to continue.

- Family visits upset some residents and were at times very difficult and emotional for the residents’ loved ones. This affected the family’s satisfaction with the facility and impression of the memory care unit.

- Residents with Alzheimer’s or dementia experience challenging behaviors when their cognitive stress level increases. Cognitive stress may have a clinical cause (infection, hunger, pain, etc.), or a non-clinical cause (boredom, disengagement or dissatisfaction with the environment).

- Staff are well-trained to handle clinical causes, but they struggled to handle non-clinical causes before the stress escalated into a behavior that required one-on-one attention to redirect the resident. Staff training did not provide sufficient guidance for these situations, and one resident’s agitation often led to challenging behaviors across the unit (and the urgent use of behavioral medications).

- Behaviors may be aggressive and outward in nature (like shouting or combativeness) or may instead be more subtle and quiet, such as rummaging, wandering, shadowing or being passive/withdrawn.

- Each resident manifests stress differently, and each resident has his or her own language to communicate how he or she is feeling, so the relationship with the caregiver is critical to understanding when a behavior is escalating into a fall risk or safety concern.

- The caregivers work hard and love their residents. However, their responsibilities centered around managing crises on the unit and completing clinical tasks, and there was little of their workday remaining for quality time and building relationships. As a result, staff retention in the dementia unit was very challenging, and many good caregivers felt helpless when trying to alleviate their residents’ anxiety.

For the second objective, the team decided to focus on customized resident engagement, with the following goals for the new program:

- Caregivers should be able to take action right away (proactively) when they see a resident becoming bored, rather than waiting for a scheduled activity.

- There should be tools available to help residents that become disengaged during a group activity.

- The interventions should be easy to initiate, and they should engage a resident without extended one-on-one assistance from the unit staff.

- The program should be accessible to families during their visits.

- The tools should address the needs of both high-functioning and low-functioning residents.

- The program should be integral to fall prevention and should foster greater teamwork among the direct care staff and activity assistants.

CUSTOM CARE

St. Leonard’s solution, the BBET program, features tools available 24/7 in a resource center on the memory care unit, including portable CD and DVD players, headphones for each resident, a DVD library, music library and a cognitive stimulating library with games and puzzles suitable for the Alzheimer’s/dementia population. Each resident has a customized “memory prop box” in the resource center where special items provided by families can be securely stored. These items are often sentimental (such as family photos, magazines, mementos, etc.) and provide comfort for the residents.

A key component of the program is the ability for staff to be able to quickly choose an item that is suited to the individual resident when an intervention is in order. To do so, the 90-plus library items are carefully coded for easy access by caregivers. Specific codes that work best for each resident are determined by developing an individual BBET Action Plan using information about the resident’s personality profile (their interests and preferences), behavior profile and cognitive functioning level.

What makes the program particularly successful is that in a short time, a caregiver can use the BBET codes in a resident’s action plan to select the appropriate intervention, initiate the intervention using guidelines taught in the BBET training and then monitor the resident while performing other care tasks. Managers report an increase in the team’s morale, because caregivers can provide emotional support as well as physical/clinical support without increasing their overall workload.

A simple tracking procedure captures the date, resident name, therapy code, start and end time, caregiver providing the therapy and comments/observations. The data is used to modify action plans as needed and is summarized for families in care conferences.

Implementing the program wasn’t without its challenges, namely, staff buy-in. Managers had to overcome the perception among staff that using the program would involve extra work. To allay staff concerns, a pilot program working with three residents was created. And when the staff realized the program benefits and time saved in proactively addressing the root causes of behaviors, they actually requested the project team to accelerate the ramp-up and bring all 18 residents into the program in two weeks rather than the eight weeks originally planned.

“Before our program the staff did not generally want to work in the Alzheimer’s unit because of the stress,” says Dr. Bharwani. “After [program implementation] there was a waiting list to work there.”

POSITIVE OUTCOMES

The BBET project team reports numerous positive outcomes as a result of the program. Within six months of its implementation St. Leonard employees reached the milestones of 1,000 interventions and 600 hours of BBET contact time with the 18 unit residents. In the first year, more than 4,000 interventions with over 3,200 hours of contact time were reported.

Follow-up research by Dr. Bharwani in conjunction with a consultant pharmacist and medical director determined that the usage of antipsychotic medications had declined significantly since the program was implemented, reports Dressman.

|

| A resident enjoys a DVD. |

And the advantages of the therapy extend beyond the activity itself, according to the team. Residents are relaxed and content after therapy and they are able to interact more during group activities and family visits. They can concentrate and eat better during meals, and they accept care more readily.

The caregivers report that residents sleep better and awaken with less anxiety. This is particularly helpful to the night shift staff who can get more residents up in the morning and provide them a pleasant experience (with an item from their prop box) while they wait for breakfast.

Family members report feeling more satisfied and optimistic about their loved one’s care experience because they are involved in new ways. They discuss the program in care conferences and they provide memory items for the prop box. Several family members use the BBET items during their visits.

“It’s been good for families,” says Terri Walker, nurse manager. “So many feel they’ve lost control. The family may be there but the communication isn’t there and it’s difficult to interact with [the resident]. It gives family members and residents a feeling of belonging when interacting with each other. And, it individualizes the person when the staff uses the resident profile.”

Dr. Bharwani shares how family members have embraced the BBET program and enjoy contributing personal items to their loved one’s prop box. For example, “A son knew his father enjoyed golf tournaments so he’d bring in DVDs of tournaments and after the father would eventually become bored with those the son—and staff, too—would bring in [new programs].”

“The staff is very much empowered to make changes,” adds Meena Bharwani, “[adapting] to the resident’s needs.”

“I was one of the staff members,” says Laura Spain, STNA, “and when you have a tool that helps your residents, you’re willing to use it.”

Dressman reports that start-up costs for the program were minimal and no new staff was added to implement the program. Existing staff sustain the program through voluntary empowerment roles. The team reports that caregivers are proud of their BBET expertise and resource center tools and feel more successful in their jobs.

“It’s made a world of difference,” says Dressman of the program. “I know the staff here appreciates a positive change. New staff can come in with minimal dementia training and work with residents like they’ve worked with them for years. Particularly when it comes to caring for people with dementia, it’s one of the more difficult areas of long-term care. Often it’s hard to feel like you’re making a meaningful difference other than keeping an eye on them. Instead, we’re providing real care and therapy.”

BBET FOLLOW-UP STUDY

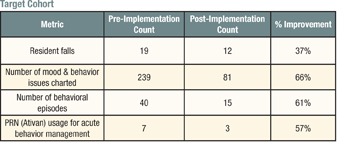

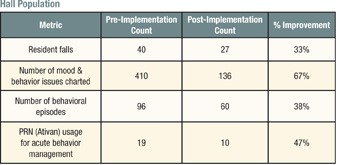

An in-depth study was conducted in 2011 by an analytical team from Wright State University comparing the baseline data six months before the BBET implementation to the data obtained six months after the launch. The metrics investigated included resident falls, charted behavior/mood incidents (and number of behavioral episodes), and usage of PRN medications for behavior management. These metrics were chosen because they represent the primary measureable elements of the residents’ quality of life (and caregiver stress) on a memory care unit.

A total of 48 residents resided on the unit during the 12-month interval (referred to below as the “hall population”). Nine residents (50 percent of the 18-bed census) stayed in the unit for the duration of the study and were considered the “target cohort.” The change in the metrics were calculated for the target cohort and hall population separately to determine if there was a difference in the benefit for the consistent residents versus the residents with shorter lengths of stay.

The results of the study are summarized in the following tables:

All of the metrics showed significant improvement in both groups and reinforced the anecdotal observations explained above. The difference in improvement percentage for behavioral episodes is noteworthy because it indicates that for the hall population, the episodes were milder (i.e., there were fewer mood/behavior issues charted per episode on average). Further analysis showed that most of these episodes were concentrated in the first 30 days after admission to the unit.

ABOUT THE OPTIMA AWARD

Since 1996, Long-Term Living has honored long-term care communities that are proactive with programs that go “above and beyond” routine care for their residents with our prestigious OPTIMA Award. It is conferred by a jury of your LTC peers from submitted entries. This year’s winner is St. Leonard Franciscan Living Community of Centerville, Ohio.

If this year’s winner sounds familiar to you, there’s a good possibility you’ve read about it in Long-Term Living over the past year and a half. St. Leonard and its innovative therapy program for Alzheimer’s residents first came to our attention in early 2011, and we profiled it in the March issue. Then, earlier this year, the program’s creator, Govind Bharwani, PhD, was voted one of our Leaders of Tomorrow and featured in the May issue.

Our congratulations to this year’s winner for all the hard work, inspired ideas and commitment to making a positive change every day in every elder’s life.

Patricia Sheehan was Editor in Chief of I Advance Senior Care / Long Term Living from 2010-2013. She is now manager, communications at Nestlé USA.

Related Articles

Topics: Alzheimer's/Dementia , Articles , Executive Leadership , Facility management