Exploring evidence-based and green design in long-term care

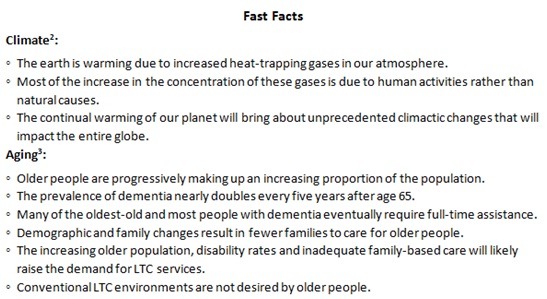

Like some critics' reaction to climate change, there are those within the field of aging who would rather pursue a “business as usual” approach than respond to an imminent exponential increase in the aged population. This article explores the application of evidence-based design for those within the long-term care (LTC) industry who want to address both of these global phenomena simultaneously.

Evidence-based design (EBD) is the process of basing decisions about the built environment on credible research to achieve the best possible outcomes.1 While, the EBD process is not prescriptive, it is benefitted by a scientific approach where one or a combination of several carefully identified inputs produce measurable and reliable outputs. The Center for Health Design envisions a world where every healthcare environment is designed to improve both the quality of care and outcomes for patients, residents and staff. Today there is a body of knowledge that supports strategies in acute care and, increasingly, ambulatory care settings that are linked to improving outcomes.

The evidence base underlying design in LTC, however, is typically not as straightforward and more difficult to locate. Care providers are continually making adaptations and innovations that respond to their clientele, local markets, reimbursement patterns and regulations; consequently, there is no one style or procedure that fits all applications. This kaleidoscope of change within the LTC industry makes it difficult to know precisely what may lead to what.

LTC researchers are looking for related evidence-based approaches that may be successfully applied to LTC settings such as those within the field of Environment & Behavior or Environmental Design Research. One place to begin looking for overall planning recommendations and specific design details tied to therapeutic goals is from a free searchable database called “Dementia Design Info.” This information has been mined from a variety of sources ranging from peer-reviewed resources to practitioner-based practices.

Additionally, pioneering care community leaders are augmenting their operational performance based on organizational development approaches, such as: CQI, LEAN, Six Sigma, Applied Positive Deviance, transformational and facilitative leadership as well as network and team-based distributed management.

The number of anecdotal LTC provider reports is growing in magnitude and frequency such that repeatedly employed strategies are being identified and are beginning to build an evidence base for the design of LTC environments and operational improvement.4 The biggest challenge continues to be the variation that exists from one LTC provider to another.

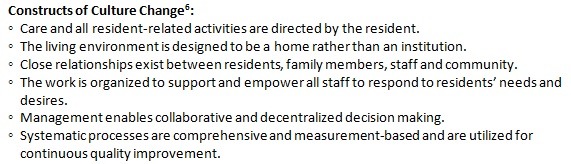

A literature review conducted in 2006 by the Colorado Foundation for Medical Care revealed six common threads, which are referred to as the “constructs of culture change.” The use of these constructs has been most prevalent among LTC providers that were fully implementing innovative organizational, environmental and operational person-centered care.

If looking for strategies associated with culture change, the Pioneer Network is an easily accessible source for information. Pioneer Network advocates for elders across the spectrum of living options; and is working towards a culture of aging that supports the care of elders in settings where individual voices are heard and individual choices are respected—whether it is in nursing homes, transitional care settings or wherever home and community may be.5

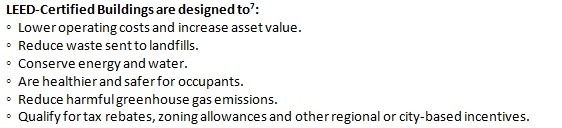

Not only are LTC providers working to incorporate person-centered care, they are also working to support the environment. The efforts of the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) intended to measure “Green Design” have culminated in LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) building metrics and rating systems for building design, construction and operation. LEED has been adapted for Healthcare environments, including licensed and federal inpatient, outpatient and LTC facilities because these environments have round-the-clock occupancy and operations and are often subject to strict regulatory and programmatic demands. Despite healthcare specific metrics, the overarching goals of the LEED certification system for Green Building Design remain consistent.7

Increasingly, LEED certification is being pursued by LTC providers and designers who are constructing both high-rise and single-story buildings. An emphasis is being placed on increasing and improving day-lighting strategies as well as using LED light layering that responds to age-related sight deficiencies. Similarly, emphasis is being placed on high-efficiency mechanical systems that may be independently controlled from single-occupancy room to room.

Interestingly, when LTC providers elect to provide person-centered care in the household model, they are inadvertently achieving greener outcomes. The LTC household model (i.e., Small Houses, GREEN HOUSE®, Cottages, etc.) is a smaller scale residential response to conventional institutional LTC. The scale of the household buildings and material selection are reminiscent of “home” rather than a hospital.8

Coincidentally, this can also mean that more materials and labor may be secured locally. Decentralized services and management, along with consistent staffing patterns, attempt to overcome the waste-related inefficiencies of centralized departmental systems. Although it is extraordinarily difficult to reliably measure social outcomes in comparison with regulated quality of care metrics, residents frequently describe achieving a higher quality of life and staff reports an improvement in the quality of their work in LTC households when compared to traditional LTC.9

Although the momentum and array of change within LTC makes it difficult to establish an evidence base for design, LTC provider’s should not pursue a “one size fits all” approach to design, given the level of contextualism necessary to serve a geographically and, often, culturally based resident population. Perhaps, then, the single most important step when applying the EBD process in LTC is to very clearly establish and articulate the vision and goals of the project prior to design and construction so that related outcomes may be identified, measured and disseminated afterward.10

In this way, the industry as a whole may capitalize upon up-to-date practitioner and designer-driven innovations and measures that continue to build upon a beginning foundation for evidence-based and Green Design that address the variations in long-term care. As the need for these environments increases, using existing research to inform design and committing to evaluating and sharing the results is critical to continue the building of this body of knowledge within the industry.

Addie Abushousheh, PhD, EDAC, Assoc. AIA, is the Executive Director for the Association of Households International as well as an Associate Lecturer at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. She is a member of Pioneer Network’s Dining Standards and Research Committees, the Treasurer for SAGE Federation and serves on the Center for Health Design’s EDAC Advisory Council. Her specialization is in organizational and environmental development and applied research in long-term care. She can be reached at addie@ahhi.org.

REFERENCES

- Center for Health Design (2013). History of EBD: 2008 evidence-based design is defined. Retrieved from: www.healthdesign.org/edac/about.

- Gleick PH, et al. (May 7, 2010). Climate change and the integrity of science. Science 328(5979): 689-90. Retrieved from: www.sciencemag.org/content/328/5979/689.full.pdf.

- National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services, & the World Health Organization. Global health and aging. Washington, DC: NIH; 2011 Oct. Retrieved from: www.who.int/ageing/publications/global_health.pdf.

- Abushousheh AM, Proffitt MA, Kaup M L. (2011). 2010 Stakeholder survey: Culture change and the household model (white paper). University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Center on Age and Community. Retrieved from: www.ageandcommunity.org/products.attachment/culture-change-and-the-household-model-9408/Culture%20Change%20and%20the%20Household%20Model%20-%20Delphi%20Survey.pdf.

- Pioneer Network (3013). Pioneer Network: About us. Retrieved from: www.pioneernetwork.net/AboutUs/.

- Colorado Foundation for Medical Care. (2006). Measuring culture change: A literature review. No. PM-411-114 CO 2006. Denver, CO: CFMC. Retrieved from: www.cfmc.org/files/nh/MCC%20Lit%20Review.pdf.

- U.S. Green Building Council (2012). LEED v2009 for Healthcare. Retrieved from: new.usgbc.org/sites/default/files/LEED%202009%20Rating_HC_10-2012_9c.pdf.

- Proffitt M, Abushousheh AM, Kaup ML. (2010). 2010 Next steps think tank: Culture change consensus and the household model (white paper). University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Center on Age and Community. Retrieved from: cac.obiki.org/products.attachment/2010thinktank-3906/2010ThinkTank.pdf.

- Abushousheh AM. (2012). Organizational & environmental complexity: Evaluating positive deviance in long-term care. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

- Kaup ML, Proffitt MA, Abushousheh AM. Building a “practice-based” research agenda: Emerging scholars confront a changing landscape in long-term care. Journal of Housing for the Elderly 2012;26: 93-119.

For further information, please refer to the World Health Organization, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institutes of Health, Pioneer Network, SAGE Federation, Dementia Design Info, the Center for Health Design and the U.S. Green Building Council.

Related Articles

Topics: Articles , Design , Executive Leadership